Exploring the Fusion: Traditional & Modern Japanese Architecture

Japanese architecture stands as a compelling testament to a profound blend of ancient traditions and cutting-edge innovation. From the serene lines of centuries-old temples to the bold, futuristic forms of metropolitan landmarks, this unique architectural landscape consistently prioritizes space, a harmonious connection with nature, and the deeply felt human experience within a built environment. This enduring philosophy has not only shaped Japan’s distinct identity but has also profoundly influenced architectural discourse worldwide.

Throughout history, visionary architects such as Tange Kenzo, Ando Tadao, and Maki Fumihiko have played pivotal roles in defining this delicate balance. Their groundbreaking works, including the iconic Yoyogi National Gymnasium, the contemplative Benesse House, and the striking Fuji Television Building, exemplify how thoughtful design can transcend mere functionality to become art. This article delves into the legacies of these master designers, the movements they spearheaded, and how their timeless principles continue to guide building styles both in Japan and across the globe, reminding us that truly great design begins with understanding people and their relationship to the world around them.

The Enduring Influence of Traditional Japanese Architecture

To truly appreciate modern Japanese architecture, one must first understand its deep roots in tradition. Contemporary buildings often subtly echo the aesthetics and philosophies of historical Japanese designs. The elegant simplicity of a Shinto shrine, characterized by clean, unadorned lines, or the meticulously planned, peaceful layouts of Buddhist temples, continue to serve as potent sources of inspiration for today’s architects.

Traditional Japanese buildings famously embrace natural, local materials such as wood, bamboo, and paper. They prioritize open, flexible spaces with minimal ornamentation, focusing instead on the intrinsic beauty of materials and the quality of light. This approach, often described as minimalism, is not merely an aesthetic choice but a philosophical one, emphasizing harmony, restraint, and a deep respect for natural elements. This principle of integrating architecture with its environment and creating serene, functional spaces remains a cornerstone of Japanese design.

Architectural historian Naomi Pollock articulates this connection perfectly: “The best Japanese architecture creates harmony between the building and its surroundings. This principle connects ancient temple design with today’s most modern structures.” This harmony extends beyond visual aesthetics to encompass sensory experiences, such as the play of light and shadow, the feel of natural materials, and the flow of air, all carefully considered to enhance the occupant’s well-being and sense of place. Concepts like Ma (the conscious appreciation of void or empty space) and Wabi-sabi (the beauty of imperfection and transience) are subtly woven into the fabric of traditional and contemporary designs, fostering a deeper connection with the present moment and the passage of time.

Pioneers of Modern Japanese Architecture

Japan has fostered a remarkable cadre of architects who have not only reshaped the nation’s urban and natural landscapes but have also pushed the boundaries of global architectural thought. Their work brilliantly fuses traditional Japanese sensibilities with innovative global ideas, creating a distinctive architectural language that is both culturally specific and universally resonant.

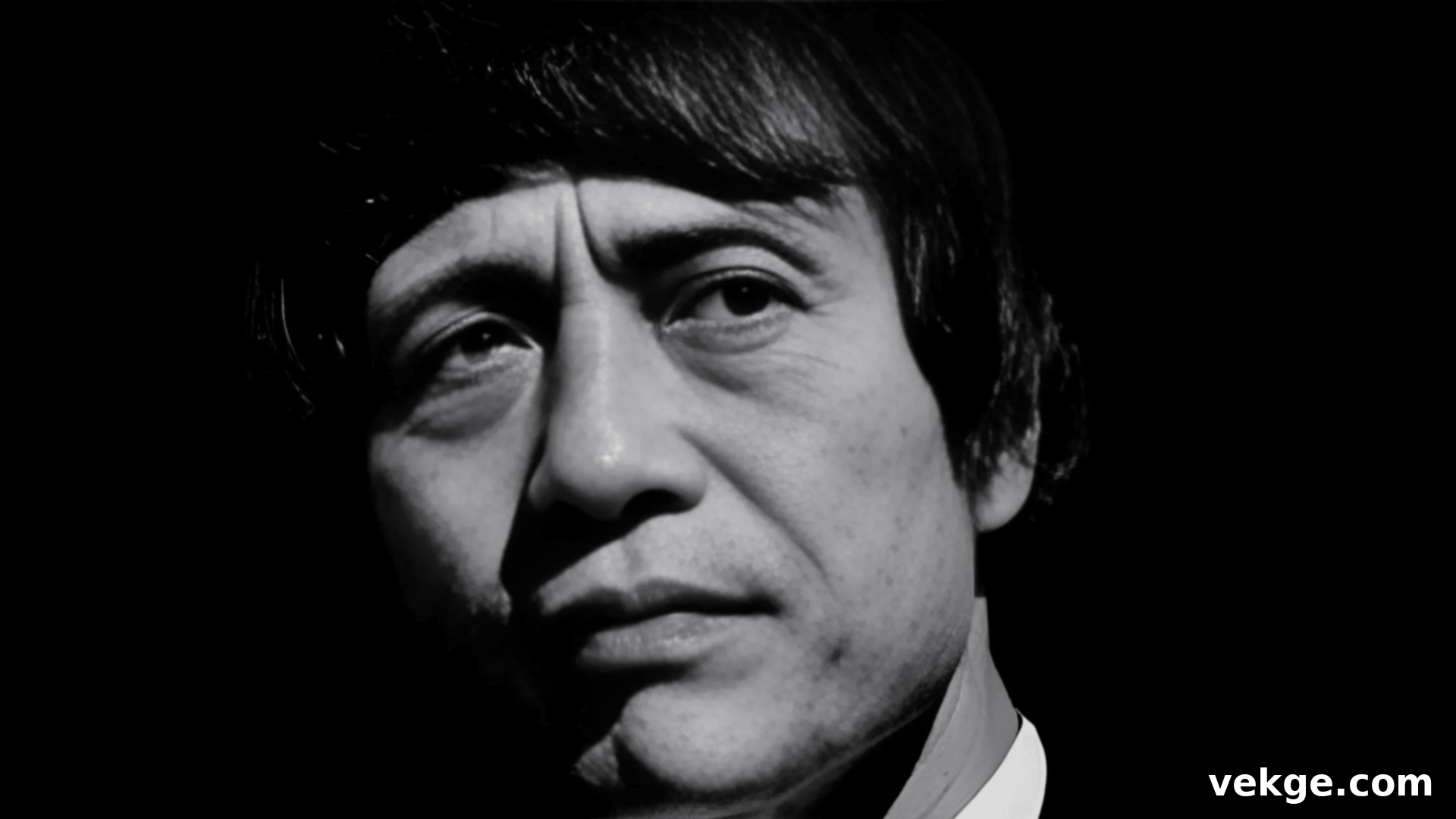

Tange Kenzo (1913-2005)

Tange Kenzo was a titan of 20th-century architecture, instrumental in Japan’s post-World War II reconstruction and its emergence onto the global stage. He masterfully blended traditional Japanese spatial concepts and aesthetic principles with robust modern materials and advanced construction techniques. Tange’s influence was particularly felt through his leadership of the Metabolist movement, which envisioned cities and buildings not as static entities but as evolving, organic structures capable of adaptation and growth.

His magnum opus, the Yoyogi National Gymnasium, designed for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, is a prime example of his genius. Its soaring, tent-like roof, suspended by a unique cable system, evokes both the dynamism of sports and the elegant curves of traditional Japanese temple roofs, showcasing how modern architecture could be both profoundly functional and breathtakingly beautiful. The Tokyo Metropolitan Government Building, with its distinctive twin towers, further solidified his legacy, becoming an instantly recognizable icon of Tokyo’s ambitious post-war identity and its aspirations for the future. Tange’s vision helped articulate Japan’s new national identity, rooted in both its past and its forward-looking ambition.

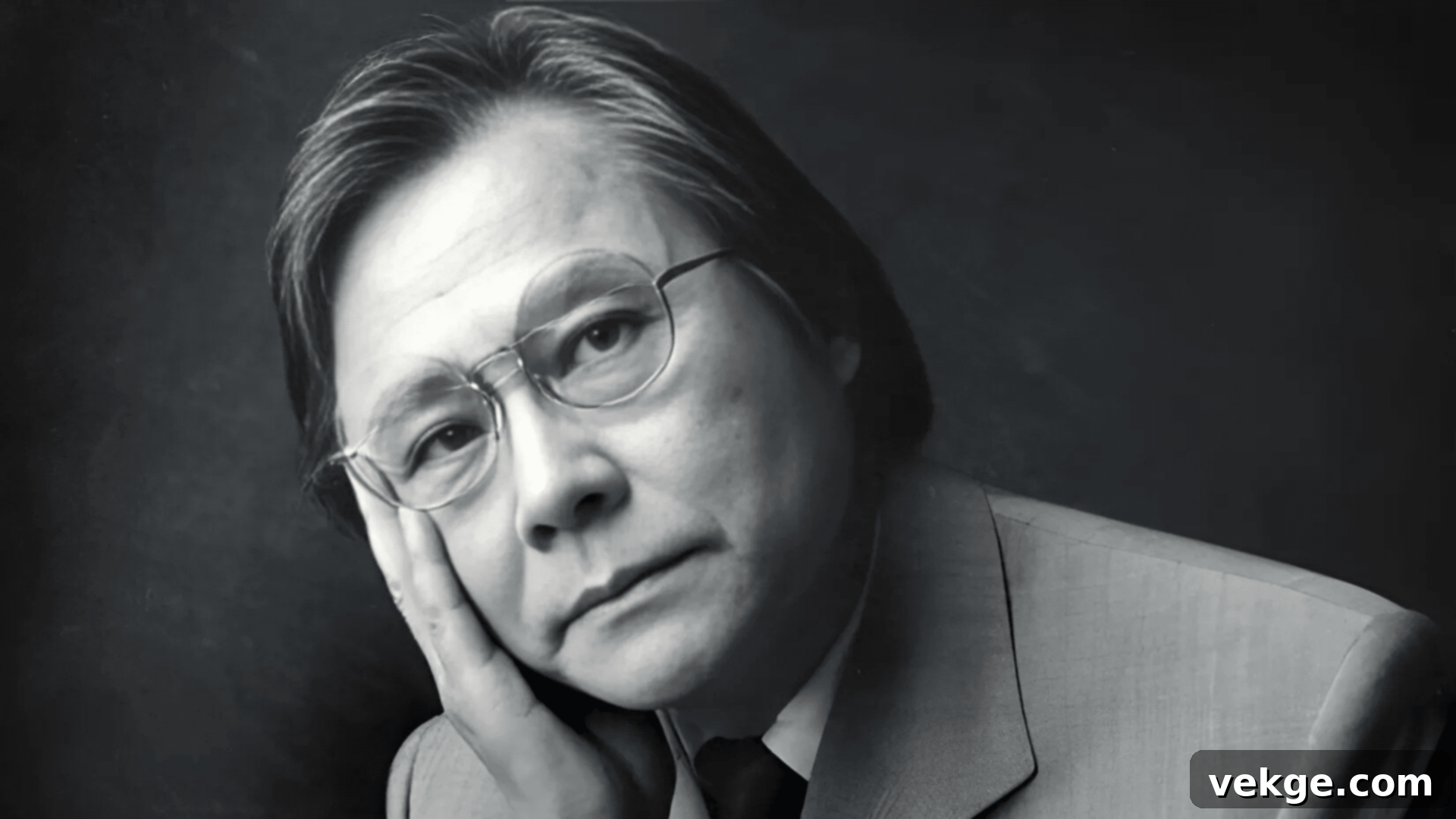

Maki Fumihiko (Born 1928)

A contemporary of Tange and a key figure in the Metabolist movement, Maki Fumihiko’s architecture is distinguished by its intellectual rigor and a profound understanding of urban dynamics. His designs combine simple, elegant forms with a deep emphasis on how people interact within and around spaces, often focusing on the concept of “group form” – the idea that individual buildings should contribute to a larger, coherent urban fabric. This philosophy prioritizes the social and experiential aspects of architecture, ensuring that his structures foster community and connection.

Notable works like the Makuhari Messe Convention Center and the Museum of Modern Art in Kyoto exemplify his approach, featuring expansive, adaptable spaces that encourage public engagement and flexibility. Maki’s architecture elegantly reflects the balance between utilizing modern materials and construction methods, and incorporating traditional Japanese concepts of light, modularity, and the seamless transition between indoor and outdoor environments. His buildings are not just structures; they are carefully orchestrated experiences designed to enrich the lives of their occupants and the broader urban environment.

Ando Tadao (Born 1941)

Ando Tadao, a self-taught architect, has achieved global renown for his almost spiritual command over concrete. He transforms this seemingly cold, industrial material into spaces of profound tranquility and contemplation. Ando’s lack of formal architectural training allowed him to develop a uniquely intuitive and powerful design approach, characterized by minimalist aesthetics, monumental forms, and an exquisite manipulation of natural light. His work often creates a powerful dialogue between geometry, light, water, and landscape.

His celebrated buildings, such as the Benesse House on Naoshima Island and the Church of the Light in Ibaraki, emphasize starkly simple geometries and the dramatic use of light and shadow to create powerful emotional and spiritual experiences. Ando famously stated, “I want to create a space for the spirit,” a philosophy evident in his works that often incorporate serene water features, carefully framed natural views, and courtyards that blur the boundaries between the built and natural worlds. His architecture invites introspection and a heightened awareness of one’s surroundings, transforming the act of inhabiting a space into a meditative journey.

Kurokawa Kisho (1934-2007)

Kurokawa Kisho, another influential figure in the Metabolist movement, advanced the concepts of modularity and interchangeability. He envisioned buildings and cities as living systems that could adapt and grow, constantly renewed through the replacement of individual components. His designs often explored themes of symmetry, prefabricated modules, and a philosophical approach he termed “symbiosis,” aiming to reconcile seemingly opposing ideas, such as ancient and modern, East and West.

His most famous project, the Nakagin Capsule Tower (completed 1972) in Tokyo, stands as a concrete embodiment of Metabolist ideals. It featured individual, replaceable living pods, a bold demonstration of flexible, adaptable architecture designed for a future of transient living. Though the original vision of regularly replacing the capsules was never fully realized (leading to its eventual demolition), the tower remains an iconic symbol of future-oriented design. Other significant works include the Fukui Dinosaur Museum and the National Bunraku Theater in Osaka, both demonstrating his commitment to blending Eastern and Western ideas and striving for a balance between tradition and innovation.

Ban Shigeru and Other Contemporary Architects

The spirit of innovation continues with a new generation of architects. Ban Shigeru (born 1957) has garnered international acclaim for his humanitarian architecture and his pioneering use of unconventional, sustainable materials, most notably paper tubes. His disaster relief shelters provide dignified housing in emergencies, while permanent structures like Onagawa Station and the Oita Prefectural Art Museum demonstrate how his sustainable approach can also yield architectural beauty and structural integrity. Ban’s work elegantly blends sustainability with aesthetic appeal and social responsibility, proving that innovative design can address pressing global challenges.

Other key contemporary Japanese architects continue to push boundaries, merging traditional Japanese elements with global trends to create truly unique and resonant spaces. The firm SANAA (Kazuyo Sejima and Ryue Nishizawa) is known for ethereal, light-filled designs that appear to float, creating a sense of openness and transparency. Kengo Kuma employs natural materials like wood and stone in innovative, intricate ways, celebrating craftsmanship and local context. Sou Fujimoto explores natural phenomena and creates structures that blur the distinction between architecture and nature, often resembling forests or clouds. Together, these architects ensure Japanese design remains at the forefront of global architectural innovation.

Key Architectural Movements Shaping Japan

Japanese architecture has been significantly influenced by several powerful movements, each reflecting a response to global trends while maintaining Japan’s distinct cultural perspective and addressing specific societal needs and challenges.

The Metabolist Movement (1960s)

The Metabolist movement emerged dramatically in 1960 with the publication of its manifesto, “Metabolism: The Proposals for New Urbanism.” This avant-garde group, comprising visionary architects like Tange Kenzo, Kurokawa Kisho, and Kikutake Kiyonori, viewed buildings and entire cities as dynamic, living organisms. They believed these structures should possess the capacity to adapt, grow, and regenerate over time, much like biological processes. Their ideas were a direct response to Japan’s post-war need for rapid reconstruction and a vision for future urban living.

Central to their philosophy was the concept of modularity, where structures were composed of interchangeable, prefabricated parts that could be replaced, expanded, or reconfigured as societal needs evolved. This radical approach was vividly showcased at Expo ’70 in Osaka, where iconic structures such as Tange’s Festival Plaza and Kurokawa’s Takara Beautilion pavilion epitomized the movement’s embrace of flexibility, bold designs, and a futuristic outlook. The Nakagin Capsule Tower, completed in 1972, remains the most celebrated and tangible legacy of Metabolist architecture, featuring individual capsules designed to be replaced every 25 years—a vision that, though never fully realized, profoundly captured the movement’s essence of perpetual change and adaptability in a rapidly modernizing nation.

Brutalism in Japanese Architecture

Brutalism, an architectural style characterized by its raw, exposed concrete and monumental forms, found a unique resonance in Japan, largely influenced by the pioneering work of Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier. His impactful visits and designs in Japan, particularly the National Museum of Western Art in Tokyo, deeply shaped the approach of many Japanese architects to this robust style, inspiring them to explore concrete’s expressive potential.

While sharing the common Brutalist aesthetic of unadorned concrete, Japanese Brutalist buildings often exhibit a remarkable degree of refinement and precision compared to their Western counterparts. Architects like Tange Kenzo and Ando Tadao did not merely use concrete for its structural strength but meticulously crafted it to create surfaces that interact dynamically with light and shadow, evoking powerful emotional and spiritual experiences. The high quality of concrete finishing, often likened to fine furniture, achieved through highly skilled formwork and casting techniques, is a hallmark of this Japanese interpretation.

Exemplary works of Japanese Brutalism include Tange’s Kagawa Prefectural Government Hall, a powerful public building designed with a civic plaza, and Ando’s profound Church of the Light, where a cruciform opening in the concrete wall allows natural light to flood the interior, creating a sacred space of immense emotional power. These structures demonstrate how a material often perceived as cold and harsh can be transformed into spaces that feel surprisingly spiritual, reflective, and deeply connected to their environment through careful attention to proportion, light, and texture.

Modern Trends and Future Directions in Japanese Architecture

Today’s Japanese designers continue to lead innovation while steadfastly honoring their rich architectural heritage. Current trends reflect a global consciousness combined with Japan’s specific environmental and societal challenges:

- Eco-Friendly and Sustainable Designs: A strong focus on reducing energy consumption, utilizing renewable resources, and minimizing environmental impact, leading to the development of highly efficient and carbon-neutral buildings. This includes passive design strategies, green roofs, and advanced material recycling.

- Advanced Earthquake-Resistant Systems: Given Japan’s frequent seismic activity, continuous innovation in structural engineering ensures buildings are not only safe but also resilient, often incorporating sophisticated damping and base isolation technologies to absorb seismic energy.

- Compact and Adaptable Urban Living: Solutions for dense urban environments, including the design of ingenious “tiny houses” and multi-functional spaces that maximize utility and comfort within limited footprints, addressing space constraints with creative solutions.

- Seamless Integration with Natural Surroundings: Architects strive to blur the lines between inside and outside, using natural light, ventilation, and carefully framed views to create structures that feel organically connected to their landscapes, continuing a centuries-old tradition.

Leading figures like Kengo Kuma are at the forefront of pioneering the use of traditional materials in refreshingly new and sustainable ways. Kuma’s design for the National Stadium for the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, which prominently featured extensive use of wood, beautifully connected modern sports architecture with deep-seated Japanese building traditions, creating a warm, inviting, and distinctly Japanese aesthetic that celebrates natural resources and craftsmanship.

Iconic Japanese Architectural Landmarks

Certain buildings serve as perfect distillations of Japanese architectural excellence, embodying both the innovative spirit and the profound cultural values that define the nation’s design ethos. These landmarks showcase the unparalleled creativity and skill of Japan’s most celebrated architects and stand as testaments to their vision.

1. Yoyogi National Gymnasium (Tange Kenzo, 1964)

Commissioned for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, Tange Kenzo’s Yoyogi National Gymnasium remains one of Japan’s most breathtaking and enduring architectural achievements. Its dramatically sweeping roof, supported by an ingenious system of suspension cables reminiscent of a suspension bridge, gives the massive structure an almost weightless, elegant appearance. This revolutionary design not only provided an efficient venue for the Olympic events but also became a powerful symbol of Japan’s resilience and triumphant post-war resurgence, demonstrating its capacity for innovation and modernity.

The gymnasium brilliantly balances functionality with unparalleled beauty. Its innovative structural solution and gracefully curved forms evoke a sense of movement and dynamism, while the interior space is vast yet inviting. Visitors consistently marvel at how remarkably modern and forward-thinking it still looks, despite being over half a century old. This timeless quality is a profound testament to the brilliance and foresight of Tange Kenzo’s design, ensuring its place as a global architectural icon that continues to inspire.

2. Fuji Television Building (Maki Fumihiko, 1996)

Maki Fumihiko’s Fuji Television Building, located in Tokyo’s bustling Odaiba district, is an unmistakable landmark, instantly recognizable by its colossal silver sphere dramatically suspended between two towering structures. Completed in 1996, this architectural marvel quickly became a vivid symbol of Tokyo’s futuristic aspirations and its vibrant media landscape, reflecting the city’s energy and technological prowess.

The building is more than just a broadcast center; it is a dynamic public space housing television studios, corporate offices, and various visitor attractions. Its highly distinctive and bold design powerfully reflects the creative energy contained within, while simultaneously making an indelible mark on the Tokyo skyline. The sphere itself contains a popular viewing platform, offering visitors breathtaking panoramic vistas of Tokyo Bay, the Rainbow Bridge, and the sprawling cityscape, effectively integrating cutting-edge architecture with urban entertainment and public access, making it a destination in itself.

3. Benesse House on Naoshima Island (Ando Tadao, 1992)

Ando Tadao’s Benesse House on Naoshima Island is a sublime fusion of a museum, a hotel, and the stunning natural environment. Conceived as a holistic experience, the building is masterfully integrated into its coastal landscape, becoming almost an extension of the island itself rather than an imposition upon it. Ando’s signature raw concrete walls define spaces that thoughtfully frame spectacular views of the Seto Inland Sea and the vast sky, creating a profound dialogue between architecture and nature that is both stark and beautiful.

Inside, art from renowned international and Japanese artists is meticulously displayed within spaces designed to enhance the impact and contemplation of each piece. Benesse House stands as a powerful testament to how architecture can elevate both art and nature simultaneously. The building’s minimalist aesthetic, careful material choices, and thoughtful integration with its surroundings culminate in a deeply harmonious and immersive experience for every visitor, transforming a visit into a spiritual journey that connects one with art, nature, and self.

4. The National Bunraku Theater (Kurokawa Kisho, 1984)

Kurokawa Kisho’s National Bunraku Theater in Osaka is a remarkable homage to Japan’s traditional puppet theater, beautifully integrating its rich cultural heritage with a sophisticated modern design. The building serves as a vital center for the preservation and performance of Bunraku, a classical form of Japanese puppet theater designated as a UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage, ensuring its continuity for future generations.

The theater’s design adeptly blends traditional Japanese architectural motifs, such as its distinctive roofline, with striking contemporary features and materials, creating a space that feels both reverent to the past and relevant to the present. This approach—balancing historical continuity with innovative adaptation—is a recurring theme in many of Japan’s finest architectural works. Kurokawa’s design not only provides a state-of-the-art venue for this ancient art form but also stands as a symbol of how cultural heritage can be preserved and dynamically presented within a modern context, ensuring its vibrancy in contemporary society.

Materials, Design Philosophies, and Global Reach

Japanese architects have cultivated a distinct approach to materials and design, reflecting both pragmatic considerations and profound cultural values. Their choices often prioritize durability, aesthetics, and a deep respect for the natural world, resulting in structures that are both resilient and poetic.

Concrete and Steel: Modern Materials, Traditional Sensibilities

While wood and paper are synonymous with traditional Japanese architecture, modern materials like concrete and steel have been wholeheartedly embraced and redefined by Japanese designers. Ando Tadao, for instance, has elevated concrete to an art form, meticulously using it to create incredibly smooth, almost sensuous surfaces that capture and diffuse light in exquisite ways. Japanese concrete construction is renowned globally for its unparalleled craftsmanship; the precision of the formwork often yields surfaces so perfect they resemble fine carpentry rather than raw concrete, reflecting an artisan’s dedication to detail.

Steel, conversely, allows for daring structural feats and dramatic, often lighter forms. This can be seen in the sweeping spans of Tange’s Yoyogi Gymnasium or the ethereal structures designed by SANAA, such as the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art in Kanazawa, where steel facilitates an open, fluid spatial experience. These modern materials are not merely functional; they are treated with the same reverence and attention to detail as traditional elements, allowing them to embody core Japanese aesthetic principles of precision, simplicity, and elegance in a contemporary idiom.

Combining Nature with Architecture: A Seamless Integration

Perhaps the most defining characteristic of Japanese architecture is its profound harmony with nature. Rather than imposing themselves upon the landscape, buildings are thoughtfully designed to integrate with their surroundings, creating a seamless flow between indoor and outdoor environments. This philosophy is deeply embedded in traditional design and continues to flourish in contemporary works, reflecting a worldview that sees humans as part of nature, not separate from it.

Traditional elements like engawa (covered verandahs or porches) blur the boundary between home and garden, while shoji screens filter light and offer subtle connections to the exterior. Carefully composed gardens are not merely adjacent to buildings but are often conceived as integral extensions of the architectural layout, becoming “borrowed scenery” (shakkei) that is framed and incorporated into the interior view. Natural views are meticulously framed by windows and openings, transforming the external environment into living artwork for those within.

Contemporary architects continue this tradition by incorporating advanced technologies and sustainable practices. This includes designing green roofs, implementing natural ventilation systems that harness breezes, and meticulously planning around existing trees and natural topography to minimize environmental impact. This enduring commitment to a symbiotic relationship between nature and architecture remains a hallmark of Japan’s built environment, fostering spaces that are both environmentally sensitive and deeply enriching for human experience.

Japanese Designers’ Global Impact and Influence

The distinctive approach of Japanese architects has earned them significant international recognition, leading them to undertake prestigious projects across Europe, America, and Asia. Their unique blend of meticulous craftsmanship, sensitive integration with nature, and innovative structural solutions brings a fresh perspective to global design challenges, often characterized by a quiet power and understated elegance.

Notable examples of this global reach include SANAA’s critically acclaimed New Museum in New York City, Ando Tadao’s profound Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, and Ban Shigeru’s striking Centre Pompidou-Metz in France. These projects demonstrate how Japanese design principles, particularly the emphasis on light, space, and materiality, transcend cultural boundaries to create universally appealing and significant architecture that resonates on a global scale.

This influence is not one-sided; foreign architects are increasingly drawn to Japan to study, collaborate, and practice, contributing to a vibrant, two-way exchange of ideas and methodologies. This rich cross-cultural dialogue continuously revitalizes Japanese architecture, ensuring it remains at the forefront of contemporary design thought and practice, ever fresh, relevant, and globally influential.

The Future of Japanese Architecture: Sustainability and Vision

As the world faces new challenges, Japanese architecture continues its evolution, steadfastly maintaining its core values: unparalleled craftsmanship, a profound connection to nature, and an exquisite understanding of spatial poetry. The future promises even greater integration of technology, sustainability, and human-centric design, building on a rich heritage while looking forward.

Sustainability and Innovation at the Forefront

Environmental concerns are a primary catalyst for innovation in Japanese architecture. Designers are intensely focused on creating buildings that consume significantly less energy, produce minimal waste throughout their lifecycle, and possess remarkable longevity. Japan’s unique geographical challenges, such as frequent seismic activity and high population density, also drive unparalleled advancements in building technology and design for resilience.

Key developments include sophisticated earthquake-resistant systems that go beyond mere survival to ensure rapid recovery, ultra-efficient heating and cooling solutions, and the design of self-sustaining buildings that generate their own power and manage resources intelligently. Furthermore, there’s a strong emphasis on developing and utilizing innovative, low-carbon footprint materials, including advanced timber construction techniques. These continuous innovations are a natural extension of Japan’s age-old tradition of working harmoniously with natural forces, ensuring that modern designs remain in perfect balance with the environment and are prepared for future global challenges.

Contemporary Japanese Designers to Watch

A new wave of visionary designers is carrying forward the legacy of Japanese architecture, ensuring its continued evolution and global impact. Junya Ishigami, for example, captivates with his ethereal structures that often appear to defy gravity, creating a sense of lightness and spatial ambiguity, pushing the boundaries of structural possibility. Akihisa Hirata delves into organic architectural forms, drawing inspiration from natural systems to create buildings that feel alive and responsive to their surroundings, often blurring indoor and outdoor spaces.

Supposed Design Office is celebrated for its inventive reimagining of traditional domestic spaces, adapting them for modern lifestyles while preserving core Japanese aesthetic values like simplicity and flow. Toyo Ito seamlessly blends advanced digital design methodologies with profound natural influences, often creating fluid, permeable structures that blur the boundaries between architecture and environment, such as his Sendai Mediatheque. These architects, among many others, are not just building structures; they are crafting experiences and visions that ensure Japanese architecture remains a vibrant, innovative, and profoundly influential force on the world stage.

Conclusion: A Timeless Legacy of Thoughtful Design

Japanese architecture transcends mere aesthetics; it is a profound philosophy that prioritizes the intrinsic feeling of spaces and their harmonious relationship with the natural world. From the stoic tranquility of ancient temples to the sleek, minimalist elegance of contemporary urban structures, the dynamic interplay of tradition and innovation demonstrates that it is entirely possible to build with both profound care and deep meaning.

The legacies of master designers like Tange Kenzo and Ando Tadao serve as powerful reminders that truly impactful architecture invites us to pause, reflect, and deeply consider how people inhabit and experience a space, rather than simply focusing on how to fill it. Their work emphasizes the importance of light, material, and the sequence of movement in shaping human emotion and connection.

As our cities continue to expand and global environmental challenges intensify, the principles embedded within Japanese architecture—craftsmanship, respect for nature, adaptability, and human-centered design—offer invaluable lessons. By embracing these timeless ideas, we can aspire to build more thoughtfully, create more lasting and resilient structures, and foster environments that are profoundly more in tune with ourselves, our communities, and the precious world around us. Japanese architecture, in its continuous evolution, remains a beacon of inspiration for a more harmonious built future.